If you want to improve your swimming, it is important to make “objective” measurements of performance and effort. Logging this information after each swim will provide benchmarks. Here are some basics on doing the measurements.

Measuring Performance

Time

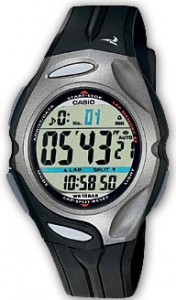

The time it takes to cover a specific distance is the most basic measurement. Waterproof watches are relatively inexpensive. Look for a watch that is lightweight, small, and easy to operate. You don’t want the big diving watch–unless you strap one to each wrist!

It should have a lap timing mode that you can use to capture various stages of your workout.

Distance-Lap counters?

By lap, we mean a “round trip of a pool.” So for a 25 yd. pool length, a lap is 50 yds. If you’re like me, while swimming longer distances (e.g.>10 laps) you can get lost in the swimming and lose track of the count. Your watch can be used as a “lap counter”. Here are 3 examples of this method.

1. Let’s say you swim 60 s. per lap (1 minute per 50 yards). If you’re swimming 15 laps and lose count, you can easily tell by the time what lap you’re on. If it reads 10:58 or 10:55 or 11:03 or 11:08, etc., you know that you have completed lap 11.

2. For a 50 s. /lap pace, 6 laps= 6 x 50 s. = 300 s. = 5:00

Or 3 laps = 3 x 50s. = 150 s. = 2:30

3. For a 55 s./lap pace, 6 laps = 6 x 55 s. = 330 s. = 5:30

Or 12 laps = 12 x 55 s. = 660 s. = 11:00

I don’t want to make this a math class, but you can mess about with your favorite lap time and come up with an interval that falls on a full or 1/2 minute interval.

Stroke Efficiency

Reducing drag and developing a good stroke technique are the keys to improvement. By occasionally counting the number of strokes (1 stroke per arm) you can see how changes in technique can affect efficiency. But simply reducing the stroke count can be deceptive. The classic “overglider” (see Swimming Smooth in the Book section) will have a lower count, but may just be coasting at a slow speed. A better measure is to add the stroke count to your time. For example, if you swim 50 yards in 34 strokes in 46 sec., your score would be 80. During another workout, you swim 50 yards in 38 strokes, but lower your time to 43 sec. That score is 38 + 43 = 81. You are working a little harder, but aren’t as efficient. On the video page, this 50 yd. free race illustrates stroke efficiency using the racing video to extrapolate some measures of efficiency (LINK to 50 yd. freestyle race.)

Measuring Effort

The simple way to measure effort is to check your pulse rate at a specific interval. As soon as you stop swimming, take your pulse at your neck (link: how to take your pulse), count the number in 10 or 15 seconds and multiply to get the beats per minute. The higher the count, the greater the effort because your heart is working harder to keep the blood moving through the lungs to provide the oxygen for your harder working muscles.

The general rule for your maximum pulse rate is to subtract your age from 22o. So if you are 50, the maximum rate is 170/min. A good target is to limit yourself to about 75% of your maximum rate. Of course, if you are a “hard core” athlete with medical clearance, you can push further. (3/21/2014 update and clarification)

An overall indication of fitness may be found in 2 specific rates:

1. Resting pulse (when you are still and relaxed–not spent by a huge effort) is lower when you are “fit”.

2. Recovery time is the amount of time that it takes the pulse to lower to a resting rate after you stop an activity. The less the recovery time, the better shape you’re in.

Self-Perception of Effort and Results

When you workout, some days probably “feel better” than others. By keeping a log, you can compare how you feel against the data that don’t lie. Some days, I feel better than others, but my performance may not reflect it. On the other hand, some days where I feel a bit tired or just not smooth, my performance may still be up to par. This disparity between perception and data is one of the more interesting things that are revealed by taking and logging measurements. It’s an important part of understanding YOUR body and improving your fitness over time.